At Rune, we're helping devs make casual multiplayer games using JS that are played by groups of friends on our iOS + Android app. There's been a lot of excitement among devs about using AI to power wacky gameplay so we added AI to the Rune SDK. To dogfood this, I decided to build out some AI games to explore what interesting gameplay could be achieved using LLMs. So I set myself a challenge. Can I build 7 multiplayer AI games in 7 days?

Here's what happened, the MIT-licensed source code and what I learnt during the process. I've recorded a little video playing all the games to give a quick feel for what they're like.

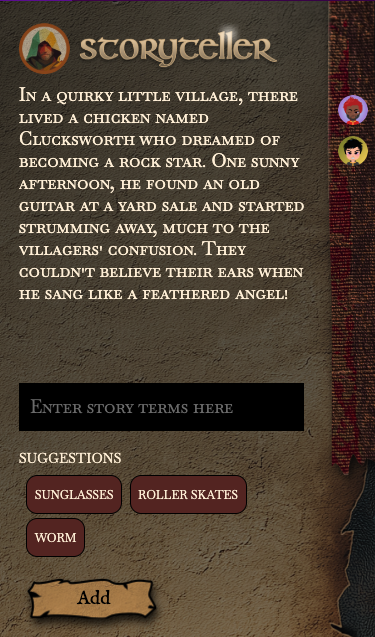

Day 1 - Storyteller AI

Play! | Kick Off | Time Lapse | Post-Mortem | Code

The first game, Storyteller AI, has the players collaboratively write an epic story together by suggesting simple terms that the AI then weaves into the story. There's no winner, or rather everyone is a winner with a brand new story created. The fun comes when people start suggesting strange and wacky terms which are attributed to them in the story.

What did I learn?

- The first game was always going to find the edges of the implementation and naturally the development ran into a few bugs which were fixed along with writing the game on the first day.

- Prompting an AI to write a story needs guidelines otherwise it just goes no where. It's important to set out clearly that there will need to be a conclusion in a fixed number of iterations.

- Players struggle to think of suitable terms, having the AI suggest some seems like an AI talking to an AI, but playtesters appreciated having the suggestions.

- The OpenAI API can take 10+ seconds to respond now and again, you have to account for that possibility in design.

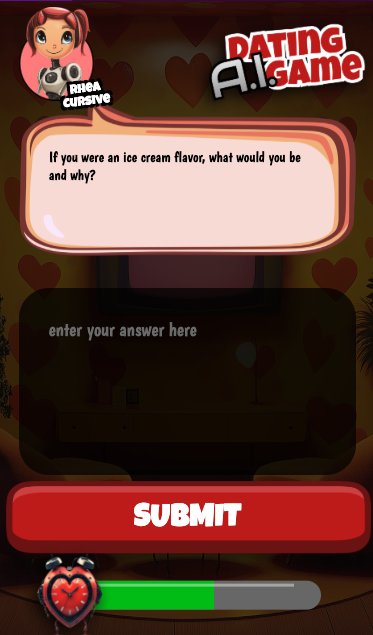

Day 2 - Dating AI Game

Play! | Kick Off | Time Lapse | Post-Mortem | Code

Definitely my favorite idea from the original list, the Dating AI Game is based on those old blind dating shows from the 70s and 80s. Players take the part of contestants attempting to win a date by answering their potential date's questions in the most fun way. The AI plays the part of the question asker and the overall narrator. Players really do seem to enjoy this one, particularly entering the most rude answer they can think of.

What did I learn?

- Players will always try to be rude / outlandish - make the choice how you want the AI to respond, don't leave it to chance!

- Asking the AI to execute 'three rounds of questions and then a conclusion' doesn't always result in 3 rounds - sometimes 2, sometimes 8. You need to be very strict and clear when the game should finish. Even if all your examples are 3 rounds, the AI may not pick up on this.

- Coming up with varied questions is difficult for the AI, especially in a constrained contextual scenario like a old school dating show when driven by examples. It often repeats the same questions in different sessions. You can get better results by explaining the reason for the example, e.g.

The example below is for structure not for content. Please come up with as varied questions and responses as possible.

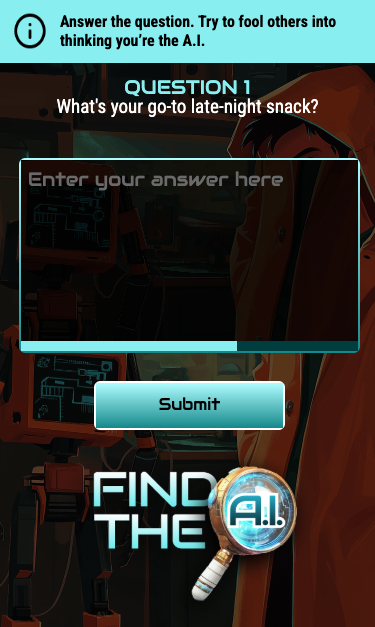

Day 3 - Find the AI

Play! | Kick Off | Time Lapse | Post-Mortem | Code

With Find the AI, I'm adapting the good old Werewolf into a simple Rune game. The AI generates a simple question, players answer it and so does the AI. The AI has been instructed to sound as human as possible including adding typos and slang. The players are then presented all the answers and have to guess which one is the AI. Having the AI act human is fun, but watching players trying to sound like an AI is really great.

What did I learn?

- Making an AI sound human isn't easy.

- AI responses tend to be elaborate and use great grammar and spelling. Humans, especially those using mobile keyboards, don't do that. They generally use short answers and they make mistakes (auto correct is everyone's friend right?).

- Asking the AI to sound more human with

Use slang or abbreviations to sound more humanresults in an obvious AI that is intentionally making a mistake every time and throwing in slang for no reason. - Giving the AI a "dial" gives the best results,

use slang 50% of the time,make an auto-correct mistake 10% of the timeseemed to give better more human responses but didn't make it into the final game.

Day 4 - The AI Times

Play! | Kick Off | Time Lapse | Post-Mortem | Code

A novel idea that was conceptualized by the team. Players are presented with a random image and asked to provide a short caption. The generative AI is then prompted to create a tabloid style front page including headline and tag line. The players then vote on their favorite story to choose a winner. The combination of abstract, quirky images and the imagination of the players results in some really wonderfully silly front pages.

What did I learn?

- Telling the AI what to value as input is really important. In this case I am feeding the AI with the player's caption and a description of the image that was provided to the player (generated offline). Initially the AI was producing essentially the same story for all players because they all had the same image.

- Being explicit about the weight to apply to the inputs helped a lot, e.g.

The player's input should be considered 10x more important than the content of the image when writing the articles

Day 5 - GIF vs AI

Play! | Kick Off | Time Lapse | Post-Mortem | Code

Probably the player favorite so far is GIF vs AI, a twist on the popular Death by AI game. The AI generates a life-threatening scenario and a GIF is chosen to represent it. Players then have to respond with how they'll attempt to survive by selecting a GIF. Finally, the AI evaluates the scenario and the provided survival GIF to determine if the player survives and selects a GIF to represent the outcome. Adding in the GIFs makes the game faster to play and the AI interpretation of the GIF can lead to unintended and funny outcomes.

What did I learn?

- The Tenor generated GIF descriptions that are provided as meta-data are often of just the first frame and don't include details of what happens in the animation. Though not accurate, in my case this leads to fun mistakes!

- The AI appears capable of generating "good" search terms based on longer textual descriptions. While AI summarization is expected to be good I hadn't expected it to be able to extract the relevant terms from the text to get a reasonably accurate GIF result from a search.

Day 6 - AI Art Judge

Play! | Kick Off | Time Lapse | Post-Mortem | Code

When adding AI capabilities to the SDK, I was quite happy that we added image analysis in as part of the same single API. The AI Art Judge game uses this to become an art critic. Players suggest a 'thing' to be drawn. They're then given a fixed time to draw a picture of the randomly-picked item. Once everyone is done, the AI evaluates the drawings based on the original input and provides an overly artsy and funny critique. It turns out AI is an expert in being pompous.

What did I learn?

- Asking the AI which is the best "...." doesn't result in an understandable result for players. The AI often doesn't pick the objectively better representation of the item.

- I ran out of time, but it may have been better to ask

what is in this imageand then get a match weight comparing that output with the original item description. - Image analysis isn't expensive as long as your images are smaller than 512x512 (generally plenty for this sort of game). Any bigger and costs go up quickly.

Day 7 - AI Emoji Interview

Play! | Kick Off | Time Lapse | Post-Mortem | Code

In the final game of the 7 days, I wanted to try out how AI interprets emojis. The AI Emoji Interview game has the AI acting an interviewer for a made up and crazy job opportunity. Players must take part in the interview but can only provide emojis as answers. The AI interprets the emojis as answers and eventually selects a player to get the job. Switching from text to emoji speeds the game up and players can still to get their point across easily.

What did I learn?

- AI can understand emoji as easily as normal text. It can even interpret the meaning of combined emoji's in most common cases.

- Similar to generating questions above, generating "crazy" jobs is difficult for AI. It tends to generate similar jobs even when asked to explore a broad search space. In hindsight it may have been better to generate 100 crazy jobs offline and used these as input rather than relying on a dynamically-generated job title.

General Observations

It's been an interest week of making games with lots of experimentation using AI through the Rune SDK. All the games were playable and fun to a level but could have been taken further and refined more. Here's some general impressions of using AI in games:

- Examples are king! Providing examples to the AI as part of the initial prompt keeps the structure of the interaction manageable.

- Structured output, e.g. asking the AI to produce JSON, seems to greatly decrease the appropriateness of the responses and limits the pseudo-creativity of the output.

- The common advice is to repeat important parts of prompts towards the end of the initial prompt. This didn't seem to have much effect this week. Adding explicit rules at the end of the prompt that re-enforced some of the initial prompt had a larger impact.

- Calling out early in the prompt that

we're playing a gameseems to result in the AI having a decent grasp immediately that there is likely to be a series of interactions. It also seems to set a tone for responses. - Using the

systemvsuserrole does have an impact.systemshould be used to set the rules of the game and the general structure.usershould be used to capture player input. Prompting a set of runes usinguserrole doesn't work as well as usingsystem. Prompting player input insystemrole works find as long as you're prefixing the input withthe user entered...but this becomes awkward quickly. Usingsystemfor player input also leaves more room open for players providing input to try and change the rules.

Preparation

Trying to create a game per day a game means getting everything in place beforehand. As I was always told, Prior Preparation Prevents Pretty Poor Performance. In this case I started with 25 ideas for AI games, whittled that down to 7 good ones and built wireframes to explore the design. Then our designer, the formidable Shane, took them and produced beautiful graphics in the associated themes.

With the designs in hand I was ready for building 7 AI games in 7 Days.

Rules

If you're going to have a challenge, you might as well set out the rules at the start so here goes:

- 7 Days is consecutive working days - weekends off!

- A day is a normal 8-hour working stint. No pulling an all-nighter and claiming the game was built in a day.

- Games start from the Rune standard TypeScript template.

- Code reuse between games is done via copy-paste of common code. No building a library and then building 7 games on it.

- All games should run in the Dev UI and on the production Rune app.

- Of course, all the games should be built using Rune!

How does it work?

Let's take a quick look at how the Rune SDK exposes AI to developers. It's quite simple to work with and that's what made it possible to churn out these games. You can check out the full documentation for more details.

Prompting the AI

To send a prompt to the AI, we invoke Rune.ai.promptRequest() from anywhere in our logic code, passing a collection of messages for the AI to interpret. Since the AI API is stateless, we need to pass it the past messages and the new ones in the request if we want it to understand a full conversation.

As you can see below, the prompt request can take both text and image prompts. In the Rune SDK, we only support passing in data:// URI's for images because we'd want to ensure the games are always available to the players, hence not allowing dependencies on external images.

Rune.ai.promptRequest({

messages: [

{ role: "user",

content: { type: "text", text: "What is Rune.ai?" } },

{ role: "user",

content: { type: "image_data", image_url: dataUri } },

],

})

Getting AI responses

The response to the prompt is received through a callback in the game logic as shown below. The response text is provided back to the logic, which can then update game state.

Rune.initLogic({

...

ai: {

promptResponse: ({ response }) => {

console.log(response)

},

},

})

As you can tell, it's a quite minimal API. The idea was to make it as easy as possible to incorporate LLMs into the gameplay of Rune games. Behind the scenes, the SDK handles the requests/responses, exponential backoff in case of request failures, etc. It's all fairly standard stuff. The real magic is in Rune's netcode for syncing players and of course in the AI itself.

Conclusion

It's been a fun, if tiring, week writing a game a day. The games themselves have come out pretty fun and I'm looking forward to how they do when they hit the 100,000's of players available on the Rune platform. Pretty much all the guidance on writing prompts generally applied to using it for games - though it is somewhat challenging to keep the AI from expanding outside the rules you want to enforce for the game. I can't wait to see what kind of AI-powered games the future holds.

Any thoughts or suggestions for how we could have made the games better? Join us on the Rune Discord for a chat!